What Is an Art Build?

Alyce WittensteinHow Art Builds Strengthen Protest Movements Through Visual Language

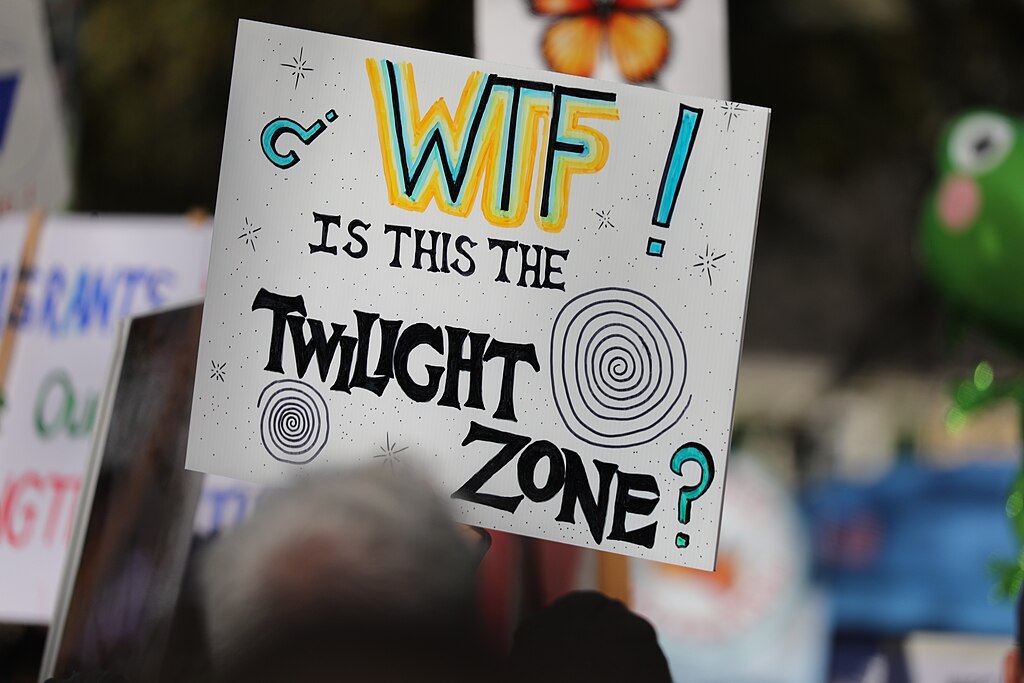

An art build is a gathering that happens before a protest, march, or rally to create large-scale, coordinated visual elements that will be deployed together in public space. Rather than focusing on a single object, an art build brings people together to construct a shared visual language—one that can hold across streets, crowds, architecture, and cameras. Some kinds of political expression can’t be made by one person, at one table, in one afternoon; they require planning, shared labor, and agreement about how a movement wants to appear when it shows up.

Art builds are a core practice in contemporary protest movements, especially in New York City, where demonstrations unfold across large, complex urban spaces and are documented instantly through photography, video, and social media—a pattern that also appears clearly in Washington, DC, Boston, Los Angeles, and Portland.

Visual Language, Built Collectively

When a movement incorporates art builds, it strengthens how clearly the action registers in public space. Repeated colors, forms, and scale make the message readable across distance, crowds, and media coverage. Instead of each element competing for attention, the visuals work together so the action is understood at a glance and remembered afterward. Over time, these repeated choices become recognizable. The message doesn’t need to be reintroduced each time—it accumulates.

How Protest Art Works at Scale

In New York City, wide avenues and dense crowds reward clarity. In Manhattan No Kings actions, large yellow banners span curb to curb, while vertical signage and crossed-out crown symbols repeat above the crowd. The same colors and forms appear again and again. The message doesn’t evolve from sign to sign; it builds density through consistency.

In New York City actions organized in Queens, that consistency is paired with place-specific imagery. Large front banners name the borough directly, while recurring illustrated elements—most notably the Resist Flower—appear at scale and are elevated above the crowd, serving as visual anchors. These images carry identity as much as text. The action can be recognized without reading anything at all.

In Washington, DC, art builds often take a performative form. Wearable sculpture, matching uniforms, and chained figures move together through institutional space. Meaning is carried through costume, movement, and choreography rather than banners. The group reads as a single constructed scene in motion.

In Boston, protest imagery draws on regional symbols. Oversized lobster costumes—immediately legible as New England—carry the message through form first, text second. Place and politics arrive together, without explanation.

In Los Angeles and along California’s coastline, art builds expand to landscape scale. On beaches, hundreds of people arrange themselves to spell messages large enough to be read from the air. Bodies become material. The message fully exists only from a distant vantage point, designed for aerial photography and wide circulation.

In Portland, long-running actions have produced distinctive, repeatable imagery that travels beyond the city itself. Symbols like the inflatable frog appear across multiple actions and formats, becoming familiar through repetition. The image carries meaning through use and reuse, signaling shared participation rather than centralized authorship.

Art Builds and Poster-Making Workshops

Poster-making workshops matter. They invite participation, help people find their voice, and are often how individuals first enter a movement.

Art builds serve a different function. They are used when a movement wants to remain legible across distance, hold together visually in large crowds, read clearly in photographs and video, and stay recognizable from one action to the next. The work is large, heavy, repetitive, and time-consuming. It takes many hands because the objects—and the images—cannot exist otherwise.

What Art Builds Do

Art builds are where movements take shape before they take the street. They are the moment when ideas stop being theoretical and become physical: banners that have to be lifted, images that have to be carried, forms that only work if people move together. Through that shared labor, a movement makes decisions about scale, color, placement, and presence—decisions that determine how it will register once it enters public space.

What comes out of an art build is not just artwork. It is coordination and shared authorship, a collective commitment to showing up in a particular way. That commitment is what allows an action to read clearly across distance, across cities, and across time, even as the people involved change. Art builds keep reappearing because they solve a recurring, practical problem: how to make collective action visible, coherent, and intentional in environments that are crowded, noisy, and constantly mediated.

An art build is where that visibility is made—before anyone ever steps into the street.